Ford Foundation Center for Social Justice

The Ford Foundation Center for Social Justice’s headquarters is a historic landmark in New York City designed by Kevin Roche of Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo Associates, was completed in 1967. The building contains approximately 200,000 square feet of offices, conference rooms, food facilities, and parking for around 250 staff. The building’s signature feature, also on […] … Read More

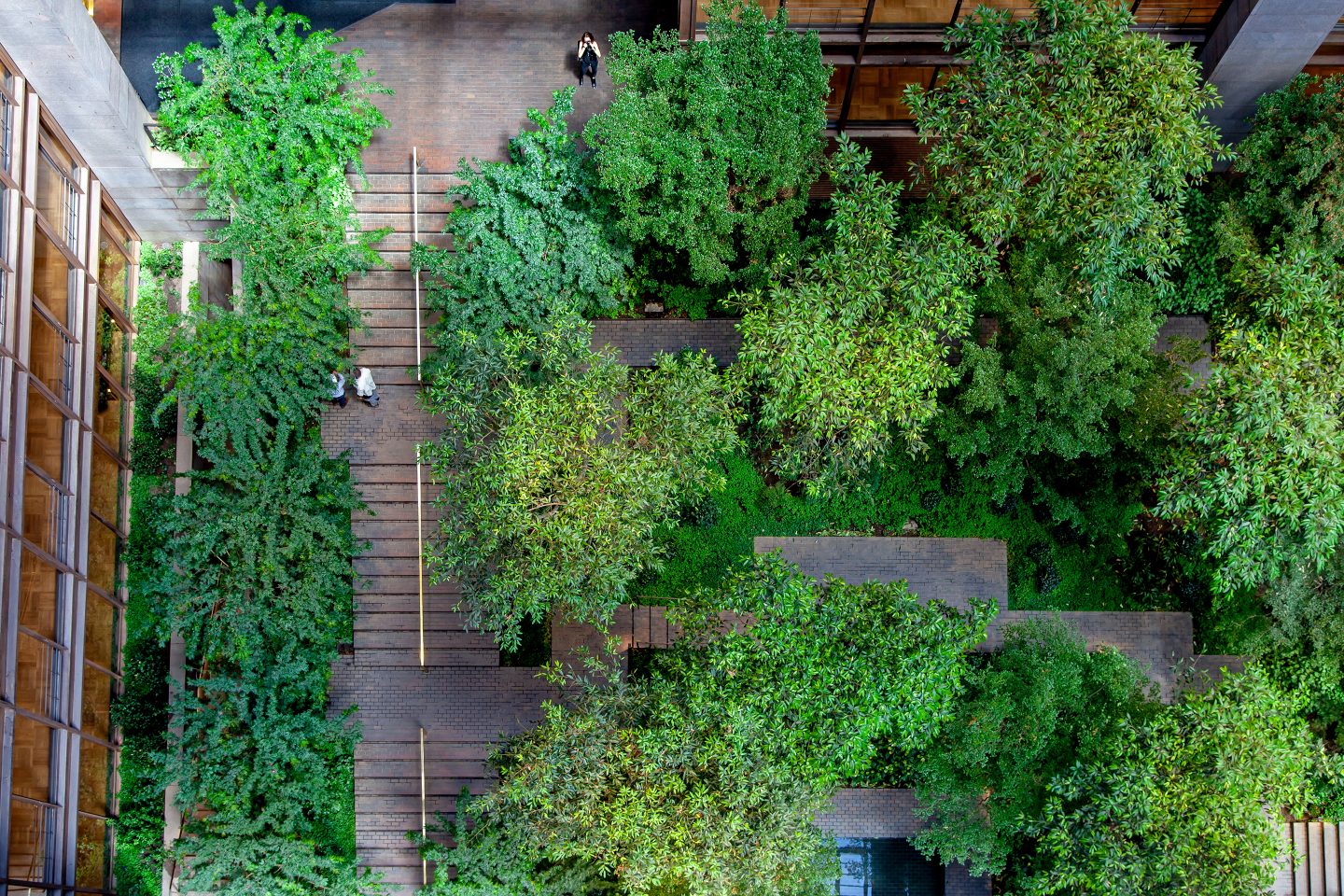

The Ford Foundation Center for Social Justice’s headquarters is a historic landmark in New York City designed by Kevin Roche of Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo Associates, was completed in 1967. The building contains approximately 200,000 square feet of offices, conference rooms, food facilities, and parking for around 250 staff. The building’s signature feature, also on the historic register, is a twelve-story, 5,290-square foot, 160-foot high, glass-walled atrium open to the public. The Atrium’s garden, initially designed by The Office of Dan Kiley, was the first Atrium of its kind in the United States. It has a thirteen-foot grade change from 42nd to 43rd Street. To best accommodate this dramatic change, Kiley’s design provided pathways at three levels and stairways which served as a throughway.

Due to the Atrium’s environment, Kiley’s design was imagined and installed as a temperate New England forest. To pay homage to the northeastern landscape, Kiley conceived a more organic planting design than what appeared in his usual modernist work. His experimental plant selections included over 40 trees, 1,000 shrubs, and 22,000 vines and groundcover. He used the plants’ bloom sequences to mimic nature and seasonality. His tree selections allotted open sightlines from 42nd Street to 43rd Street for light penetration while also complementing the Atrium´s monumental scale and creating an intimate garden experience. The understory provided color, fragrance, and texture. The main tree species, Magnolia, Eucalyptus, and Cryptomeria, were chosen for their presence and form. Jacaranda and Pyrus were used to enhance the space through color and texture. Ferns and grasses were used to create patterns like dappled light on a forest floor.

Despite Kiley’s expectations and aspirations, the inherent challenges in the Atrium, light requirements, extreme slopes, temperature, and humidity constraints, hindered the full success of the landscape over time. Many of the original plants had not developed fully due to pests and environmental conditions, which impeded growth and resulted in planting replacements that diverted from Kiley’s vision; Jungles’s intention was to restore it.

At the outset of the renovation in 2015, the Atrium looked ad hoc and overly dense, with no direct sightlines. Jungles performed an extensive analysis of the original plan, comparing plants that could survive in the Atrium’s harsh environment. The team was adamant about following Kiley’s lead and planting directly into the soil. Driven by deliberate planting relationships, the intended planting strategy was executed so that the garden would grow stronger with time, allow a careful study of the garden’s evolution, and combine Kiley’s vision with scientific innovation.

Creating a new ecosystem mindful of the original design required several innovative approaches. Consequently, the team made several key adaptations: installing new grow lights, pre-purchasing plants, and acclimating the trees. Fitting the new grow lights presented an initial challenge due to the historic nature of the building. Collaboration with the MEP engineer and architect allowed the team to anticipate the Atrium’s conditions and work to acclimate the trees accordingly. The acclimation period trained trees to thrive in low light conditions. The trees were purchased, root pruned for hardening, then bare-rooted and transplanted into custom-fitted boxes. The thirteen-foot grade change and resulting steep slopes between paths required technical intervention for tree planting. The eight-month acclimation period had to take the Atrium’s slope into account. The team used the Missouri Gravel Method during their acclimation to create more fibrous root growth and aid the trees’ adjustment. The exact slope of the gravel in the box reflected the tree’s final location. The trees remained in their boxes and under shade for the duration of the process. The trees would weigh less and could potentially be “walked” into the Atrium. However, due to the historical significance of the building, access was only available at a 9.5’ by 11’ door on 42nd Street.

Limited availability of appropriate plant material vital in re-envisioning Kiley’s design required tagging larger than anticipated trees. The plan of “walking in” all the trees became obsolete. Together with the help of a talented landscape contractor, the team revised the installation plan by bringing a crane into the historic space without damaging the original brick paving. The larger trees were installed by crane, moving, and working them around sizable trees and delicate garden paths. The use of geofibers as a soil additive to hold slopes as steep as 1:1 enabled the larger trees to be planted. The understory mimics Kiley’s with ferns, blooming shrubs, and groundcovers.

As a result of the team’s innovation, adaptability, and close collaboration during both the design and construction phases, the project is a success. The Atrium today is again as Dan Kiley envisioned it.

Year of Completion

2019

Location

New York, New York

Local Landscape Architect

SiteWorks

Soil Design

James Urban

Architect

Gensler

Landscape Contractor

Alpine Construction & Landscaping Corp.

Irrigation

Northern Designs LLC

Photography

Barrett Doherty and Garrett Rowland

Previous

Miami Beach Botanical GardenNext

The Modernist Garden